A soft collision of ancient glam and sexy ruin marks the recent collaboration between Julia Rose Katz and Devon Dikeou—both recipients of the 2025 Rome Prize in their respective fields: Julia, winner of the Anthony M Clark Rome Prize for Renaissance and Early Modern Studies, and Devon, the Jules Guérin Rome Prize for Visual Arts.

While on fellowship at the American Academy in Rome (AAR), they were paired in a program called Shoptalks, a public forum for Rome Prize Fellows to share their current and ongoing work with each other. The result of their working in collaboration was an idiosyncratic limited-edition book of images sourced from Renaissance paintings, Ancient Roman sculpture, film stills, fashion, and photography as well as their own photographs and artwork. The only text that appears are statements from Julia and Devon, and chapter headings: Entrance, Break, Pop, Part, Joy, Rock, Exit.

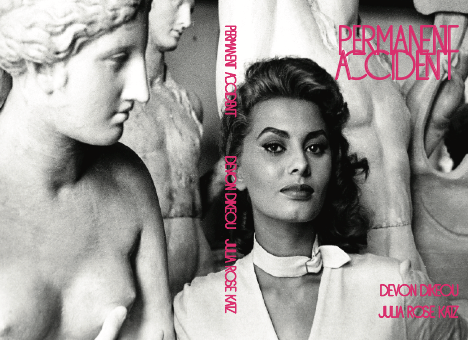

Permanent Accident—a seemingly enigmatic title that was taken from a glitter spill in the studio—is both artwork and book, and one look at the cover alone tells you everything you need to know about how to read it: a young Sophia Loren posed next to a Roman statue, looking with catlike self-possession directly into the camera as she sneaks one hand toward the statue’s breasts as if to make a grab at them.

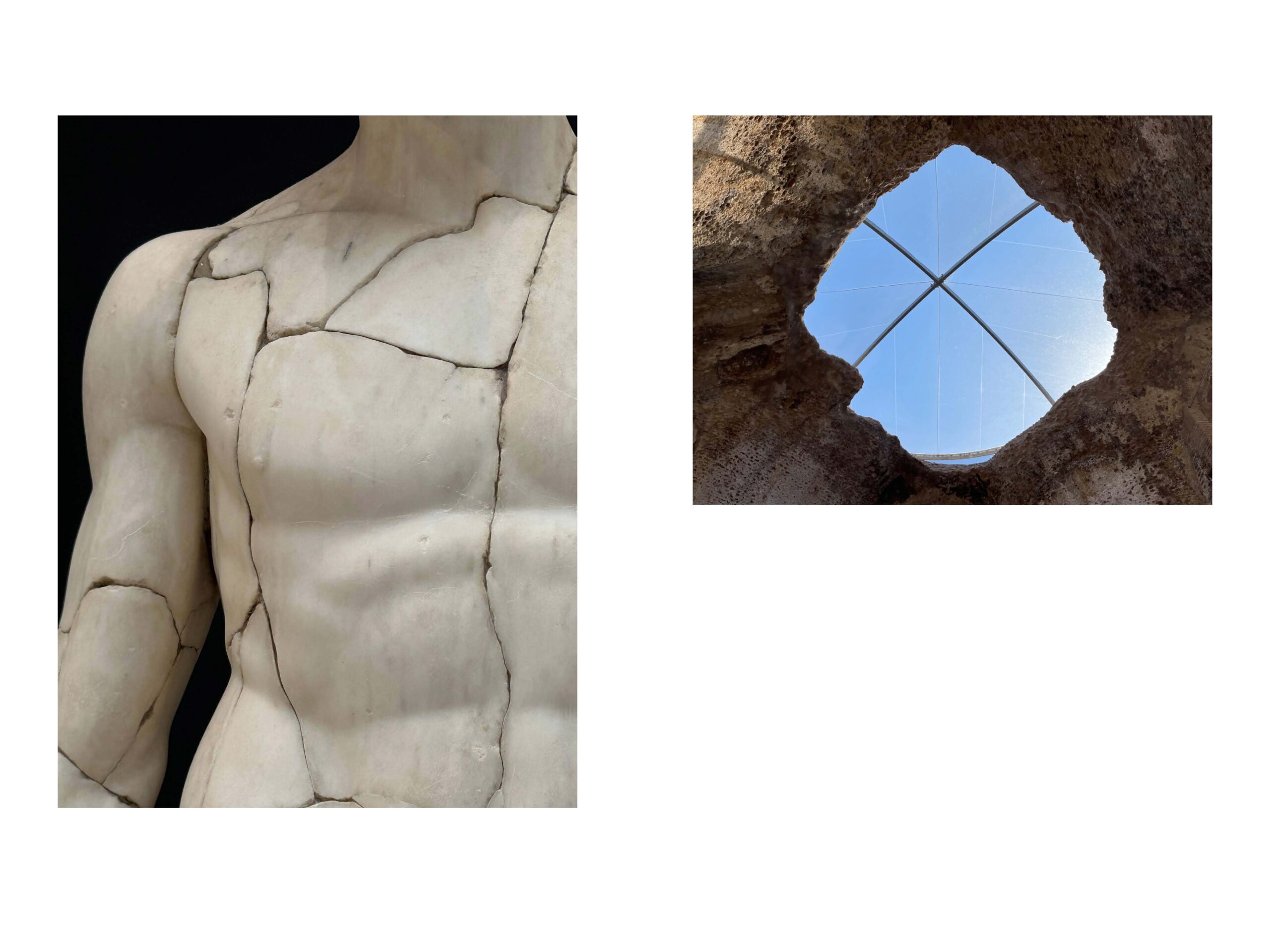

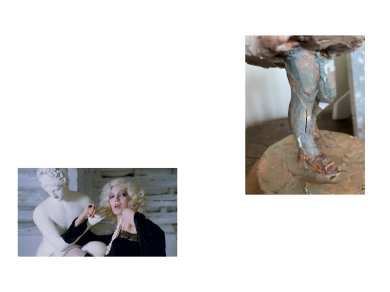

Which is to say, these images talk to each other—fractures appearing on the torsos of figures amidst ancient ruins, a Saul Leiter photograph of a woman examining cracks in the sidewalk, doorways and gates to devotional altars. It’s more poetry than narrative, more art than history, more history than narrative.

In conversations leading up to their Shoptalk, they realized that they shared a connection to artist Lizzi Bougatsos–Devon as the largest collector or her artwork, and Julia whose work is influenced by personal experiences that evoke themes of breakage and repair as well as the use of found objects, also characteristic of Bougatsos’ work. As part of their Shoptalk, Devon brought Self Portrait, a mold of Bougatsos’ leg in ice to the entrance hall of the Academy.

Devon Dikeou & Julia Rose Katz

as Interviewed by Rachel Dalamangas

During your AAR Shoptalk where the book-in-progress was presented, I noticed the concept and references of breakage and repair in the sense of (art) restoration, the body, and even the way that the images are presented breaks their original framing. How does the title Permanent Accident apply to your contributions to the book? How was the title decided?

JRK: We came up with the title together over a meeting in Devon’s studio. I mentioned loving the glitter that covered a book layout displayed on her table. Devon told me she had mistakenly spilled glitter all over the studio, and that it had become “the most beautiful permanent accident.” This was the genesis of the book’s title, but it does have a deeper meaning too. The idea when compiling the book was to convey a sense of randomness, so the selection of images appears almost accidental. Of course, it is not actually accidental at all, but we wanted it to feel that way. In reality, the images are carefully chosen, organized, and arranged, but we intended the rationale behind the selections to be invisible.

DD: Another title could be Invisible Accident. Invisible and Permanent are diametrically opposed. One must look, truly look, not just glance, to see. Sounds a little too phenomenological but it’s relevant. When Cezanne is looking at those oranges and realizes the next time he looks, they won’t be the same . . . It’s both a still life and a phenomenological realization that brings on Cubism. (Cezanne’s Doubt, Maurice Merleau-Ponty). We look at that glitter, hoping it stays permanent. “All that glitters is gold”, right . . . But that glitter from a second ago will float . . . As glitter does, and become slightly lost in the diaspora of life. Invisible, I know the invisible, the back door, the place uninhabited, the forgotten and yet treasured . . . The land of misfit toys . . . to which I most belong. And I would hope my compatriot and foil in glitter among all things to be there: Julia . . . Who knows the permanent.

It interests me that you both work across disciplines as creative thinkers: Julia as an art historian and artist; and Devon as an artist, curator, and editor. How did your backgrounds inform the creation of the book?

JRK: I don’t consider myself an artist. My interests are curatorial, so I treated the book as a curatorial project. I considered each image an object, situated in relation to what precedes and follows it. We each provided half of the images in the book, and my contributions comprise my own photographs, as well as found images that relate to the book’s themes and my personal interests as an art historian.

DD: I am an artist. But my practice encompasses both editing/publishing zingmagazine, a curatorial crossing, (est 1995 Ongoing) and collecting and assembling the Dikeou Collection (est 1998 Ongoing) . . . All three of which are very much curatorial by nature. And curating is a collaborative endeavor . . . In my mind, Julia and I set out on an adventure, initially on the platform of a book. But deeper than just the book, our collaboration took on another voice in the making of Shoptalks: and that was doing a real event, a real and literal presentation of our thought process. That was bringing in an ice sculpture by Lizzi Bougatsos from Dikeou Collection. It’s a leg, Lizzi’s leg, and the sculpture lasts about four hours. In the end, it can/needs to be broken. Inherent Vice. Its own medium is the cause of its destruction. So both the book and culminating moment of the performance were an exchange of ideas and images, thoughts, hopes disappointments and eventually . . . As that’s always what happens with books and performance, it’s finished, and once the exhilaration of the publication has been exhausted, there’s that . . . And performance is that friend dusts at the bar. Sometimes you may reunite . . . But books live on in their small capacity beyond the life of a show/exhibition/performance . . . Those sage words were spoken to me Kenny Goldsmith as I was delivering zingmagazine to Paula Cooper, which at the time, I knew will never get to her . . . Solice . . . Scott Joplin chimes in, with poetic and clear love of just trying to create, collaborate, and communicate . . .

It seems to me that there’s a kind of conversation taking place between images that I can partially understand just enough to follow a pattern although I am also unsure how much I’m projecting meaning (like being an American with very little Italian in Rome!) The images also cover a lot of art-historical-cross-disciplinary ground including ancient statues, fashion, black and white film stills, pop, and contemporary art (including your own). Can you share some insight on your choices of images and how the book was arranged?

JRK: If you’re projecting meaning, then you’re responding to the book exactly as you should! Sometimes our approach was more aesthetically driven, other times it was more playful. It was very important to us that the images in each spread converse with one another, but it’s your job as the reader to uncover the hidden significance. My work as an art historian focuses primarily on ideas of bricolage—the combination of ancient objects into new compositions—all of which directly inspires and informs the assembly of images in Permanent Accident.

DD: Sections: we divided the book into sections/chapters with input from both of us in terms of both image selection and placement under section titles, and then as a juxtaposition with each other. Those section titles we settled on are: Entrance, Break, Pop, Part, Rock, Joy, Exit. If a reader finds a clue here or there, by chance or projection, we might create a memory, a pretty important exchange between reader, curator, editor, artist, and audience.

Ok, very simple and yet very hard question: How does one “read” this book? It’s interesting because the images are all out of their original contexts (your studio art, reproductions of museum objects, and gallery pictures), and the book itself is a new original work of art. In a way, it only makes sense for it to exist as an actual object (and not an ebook) in a time where content is getting hoovered up by the great maw of the internet, which tells me physicality, especially regarding how the images are presented in a two-page spread, matters a great deal here.

JRK: Yes, this is absolutely correct. The book would not work the same way in a digital format. The tactile experience of holding the book, flipping through its pages, and engaging with it as a physical object is crucial to our conception. We live at a time when we are inundated with images, and our intention here was to bring value and focus to each page. Our hope is that the reader brings their own meaning to these visual compositions by montaging together disparate elements.

DD: Reading is subjective. Of course, Gertrude Stein and more recently, Calvino, Kundera, Cortazar, Auster among others teach us this. The reader in the postmodern world, much less the universe of magical realism, is an active reader, who participates with their interpretation of the published work and goes down whatever rabbit hole that may lead. I hope it’s a good as Alice’s, which is both real and unreal.

I LOVE the cover of Sophia Loren in Rome with the statues and of course it’s very clever the way the image wraps around the cover. It winks at the sense of humor and playfulness you both brought to this project. Even the decision to use “shocking pink” for the cover text teases out a little bit of scandalousness and sexiness, and no small amount of glam and feminine confidence. How did you arrive at the truly brilliant choice of using this particular image?

JRK: We were perusing photographs of old film stars and came across this shot of a young Sophia Loren surrounded by casts of ancient sculptures. The image relates to my academic work on the revival of antiquities in Italian cinema and our common interest in popular culture, specifically the women who defined that culture in the twentieth century. The use of the color “shocking pink” for the text draws on the history of the color by Elsa Schiaparelli, who adopted it for her brand and for the packaging for her perfume, designed with a then scandalously shaped bottle that recreated Mae West’s torso. “Shocking pink” became representative of female strength as well as the avant-garde in fashion, and this 1930s history inspired us as we developed the book, which aims to confuse or shock with its sometimes unclear juxtapositions.

DD: Sophia is there, present in all of Italy. Not like how you might see her in little Italy. She’s just there, permeating the air and telling you she is its ethos . . . Choosing the cover is perhaps the most important task of editors/curators . . . In the same way when I select a cover zingmagazine, where I go is to the NY Picture Library, and physically going to the building, and search specific topics, in folders, under the fluorescent lights for something in the long lost selection of images by some picture editor/librarian—nameless—I might find an image that might pertain to that which should be conveyed. But Rome itself is a library. A visual, architectural, filmic library and as you peep, revere, absorb . . . Sophia shines bright . . . Coddled in and next to the gods, drinking their nectar, how could you resist. Why shouldn’t she take Front, Back, and Spine.

Rachel Dalamangas

New York, New York

September 2025

Image Credits:

Man Ray

Lina Mertmüller

Deborah Kass

Luigi Ghirri

Patricia Cronin

E.V. Day

Hiroshi Sugimoto

several photos taken by the authors

Devon Dikeou and Julia Rose Katz

Sophia Loren at a studio in Rome, 40.6 x 26.7 cm © Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo.

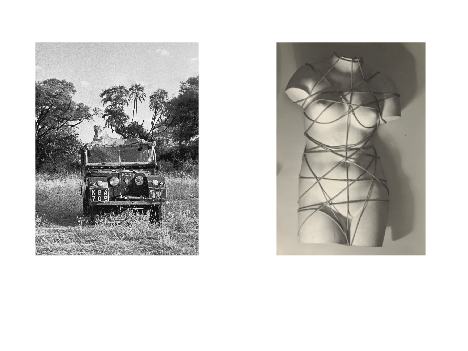

Elsa the lioness of Born Free fame lying on the roof of the Adamson’s Series 1 Landrover, Kenya. 26.5 x 34.5 cm, 2018 © Mark Boulton / Alamo Stock Photo.

Man Ray, Vénus Restaurée (Restored Venus), 1936. Gelatin silver print, 16.5 x 11.4 cm (6 1/2 x 4 1/2 in) © Man Ray Trust ARS-ADAGP.

Deborah Kass, Blue Barbras (The Jewish Jackie), 1992. Silkscreen ink on syntehtic polymer paint on canvas, 91.4 x 114.3 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Luigi Ghirri, Amsterdam, 1980, from the series ‘Still life,’ 2011. Blue felt-tip pen on paper, 75 x 56 cm (20 x 24 in). © The Estate of Luigi Ghirri. Courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York and Los Angeles, and Mai 36 Galerie, Zurich and Madrid.

Patricia Cronin, Shrine for Girls, Venice Saris, 2015. La Biennale di Venezia, 56th International Art Exhibition. Photography by Mark Blower. Courtesy of the artist.

Luigi Ghirri, Pantheon, 1982. Vintage chromogenic print, 32 x 47 cm (12 x 18 1/2 in). © The Estate of Luigi Ghirri. Courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York and Los Angeles, and Mai 36 Galerie, Zurich and Madrid.

E.V. Day, Bombshell, 2000. Dress reproduction of Marilyn Monroe’s costume in the film “The Seven Year Itch,” 16 x 16 ft. Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Courtesy of the artist.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Carignano, Torino, 2016. Gelatin silver print, 1492.2 x 119.4 cm (58 3/4 x 47 in) © Hiroshi Sugimoto. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco Lisson Gallery.